Respighi is famous for his Roman Trilogy, three sumptuous orchestral tone poems conjuring the fountains, pines and festivals of Rome.

His native Italy also inspired one of his most delicate pieces, the Botticelli Triptych (or Trittico Botticelliano, in the original Italian). Also known as Three Botticelli Pictures, each movement of this radiant 1927 work for orchestra takes its cue from a painting by Sandro Botticelli – born Alessandro di Mariano Filipepi c1445 – one of the leading artists of the Italian Renaissance. Few composers have so skilfully and appealingly turned great art into great music.

Why did Respighi compose his Botticelli Triptych?

Relatively little is known about the background to its composition. What is certain is that the project sprang from Respighi’s association with Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge, a wealthy American arts patron and music lover, who over the years commissioned a host of notable works, including Copland’s Appalachian Spring, Britten’s String Quartet No. 1 and Stravinsky’s Apollon Musagète.

In 1925, she financed Respighi, by then in his late forties and well established in his homeland as a composer, to tour the United States. On his second visit in 1927, he attended a concert held by Coolidge at the Congress Library in Washington – possibly inspired by the building’s Italian Renaissance-style façade, Respighi announced he would write a piece based on Botticelli paintings and dedicate it to Coolidge. That September the Botticelli Triptych was premiered at the Konzerthaus in Vienna, in a concert sponsored by his American patron. It was, noted Respighi’s soprano wife and biographer, Elsa, ‘a good performance and quite well received’.

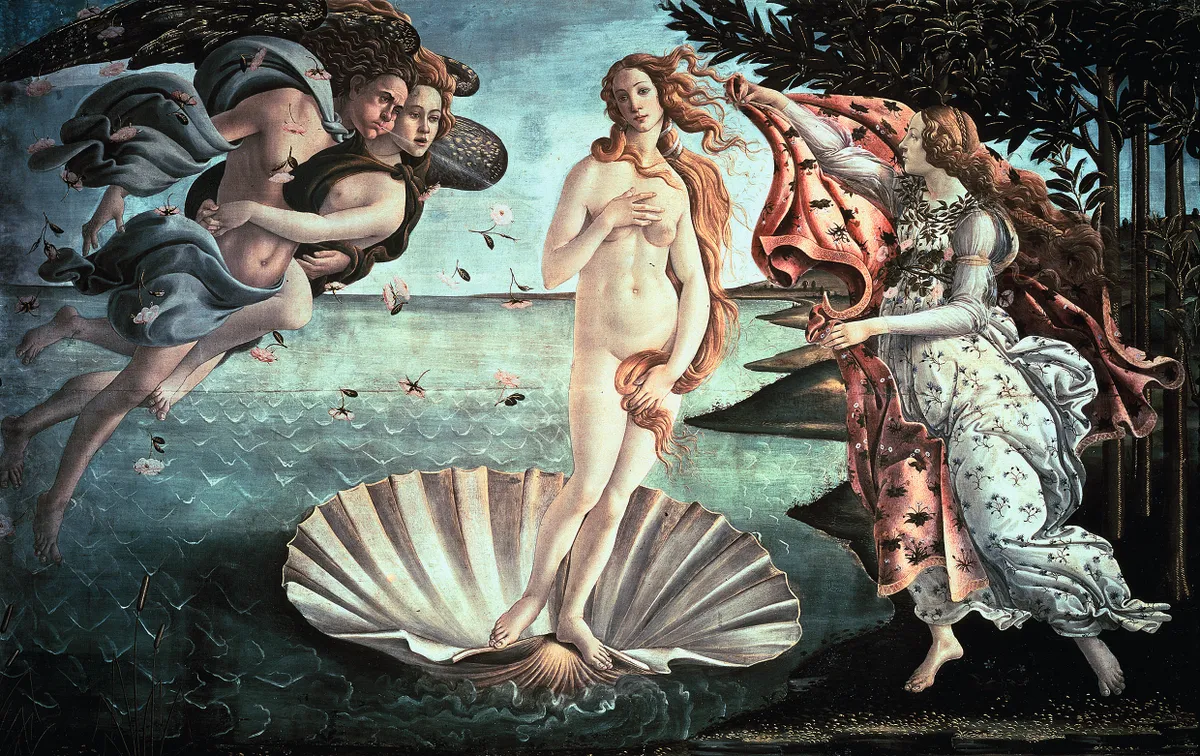

While Elsa’s words suggest nothing out of the ordinary, the art and music tell a different story. The Botticelli pictures all hang in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, Italy, crown jewels in a magnificent collection of art. For his sources, Respighi picked two of the artist’s best-known pieces, La Primavera (Spring) and Nascita di Venere (The Birth of Venus), plus a third slightly less well-known one, Adorazione dei Magi (Adoration of the Magi). All three pictures are painted with tempera, a favourite among artists until the invention of oils. Made from dry pigments bound together with oil and egg yolk, tempera dried quickly, lasted well and resulted in vivid colours – a quality more than matched by Respighi’s masterful orchestration.

A guide to the music of Respighi's Botticelli Triptych

Although Botticelli’s three paintings don’t form an official set or tell a particular story, they all explore themes of birth, awakening and arrival. Respighi turns to Spring first, a beautiful painting completed around 1480 which draws on classical mythology and celebrates nature.

Nine figures fill the picture, standing in a grove of orange trees with, according to the Uffizi’s art historians, at least 138 accurately depicted species of plants. There are many different interpretations of the painting, but for Respighi the focus was spring itself. Elsa summed it up in a programme note: ‘Spring is personified by the figure of a woman. She comes forward scattering flowers, while all Nature round about her awakes. Young women, wreathed with flowers, weave dances, the birds sing. Trills, songs and dances follow each other in the orchestra with rhythms of joy.’

From spring, we move to winter. The centrepiece of Respighi’s triptych is Adoration of the Magi, based on one of Botticelli’s many depictions of the nativity. This resplendent painting of 1475 is rich in colour, detail and history. On one level, it depicts a familiar scene, with Mary, Joseph and the baby Jesus placed high in the centre. Three finely dressed men pay their tributes to Christ, flocked by well-wishers either side. Yet there’s another layer of meaning to be found. The three Magi? They are Cosimo de’ Medici, once the powerful ruler of Florence, and his two sons Piero and Giovanni. And amid the brilliantly painted crowd, full of life and expression, we can even spot the painter himself, on the far right in an ochre robe, looking directly at the viewer.

So which elements does Respighi depict in his music? Rhapsodic bassoon and oboe lines, peppered with so-called ‘exotic’ chromaticisms, evoke the East, home to the three kings. Composer, like artist, draws the past into the present. Over atmospheric sustained low strings, flute and bassoon play Veni, veni, Emmanuel, the ancient Advent plainsong. Pastoral woodwind solos evoke shepherds’ songs, while bells, triangle, celesta and harp add a celebratory feel. Respighi also echoes the symmetry of Botticelli’s painting, bringing the bassoon solo back to usher in the final section. Here the bassoon plays a melody based on Tu scendi dalla stelle, an 18th-century Italian carol: ‘From starry skies descending, Thou comest, glorious King’.

To close, Respighi returns to Greek myth. The dramatic arrival of Venus, born from sea foam and propelled to land by Zephyrus, inspired Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus, surely one of the most famous paintings in the world. The image of the Goddess of Love and Beauty, a luminous, naked figure in a huge scallop shell, has become iconic, inspiring magazine covers, pop singers, contemporary artists – and composers. Respighi’s Venus wafts in on a wash of shimmering strings, evoking undulating waves. Flute and clarinet flutter by, soft as the breeze. There’s a transparency to Respighi’s orchestral palette that matches Botticelli’s aquatic vision. A sense of expectation and awe grows, and a melody builds to become, in Elsa’s words, ‘a hymn to eternal beauty’.

The best recordings of Respighi's Botticelli Triptych

Neville Marriner (conductor)

Academy of St Martin in the Fields

Warner Classics 2435693585

Respighi’s trick was to capture the essence of Botticelli’s paintings. That’s also what makes the very best of a good bunch of recordings of the Botticelli Triptych stand out. The finest performances relish Respighi’s orchestration (he did study with the master, Rimsky-Korsakov, after all), the music’s wonderful colours and its descriptive qualities.

Yet, just as Botticelli added layers of meaning to his paintings, so do the truly rewarding recordings also find something deeper below the surface. For spirit and a real joy in Respighi’s musical reinterpretations, look no further than Neville Marriner’s recording with his Academy of St Martin in the Fields, made back in 1976 in Abbey Road Studios for HMV, and repackaged since by Warner Classics.

With a fizz of sound whipped up by scurrying strings, followed by the heralding of horns and trumpets, there’s a delicious sense of excitement and expectation right from the start of ‘Spring’. All the jubilation of the season is here, ensemble is taut, and the playing still comes up irresistibly fresh all these years later. And while Marriner and his band capture a pastoral mood, the music never gets bogged down and instead always presses ahead at a swift pace.

‘Adoration of the Magi’ begins equally compellingly, thanks to the shaping and phrasing of the bassoon and oboe solos. Woodwind and strings are well balanced, and even if there’s the odd unwelcome edge to the string tone, the immediacy of the performance more than makes up for it. The Veni, veni Emmanuel plainchant feels fully integrated into the movement, rather than like a postcard from the past, and when the music moves into its more driven central section, the pacing feels right.

The violin solo glints in a lovely fashion. What really elevates this performance, though, is its emotional impact. Other recordings emphasise more surface qualities, but Marriner ensures that, by the time the bassoon returns to sing its gentle lullaby, we do feel as if we have glimpsed a miracle.

Marriner’s recording is also one of the few that really evokes the luminous quality of ‘The Birth of Venus’, with transparent textures and playing that seems to float and shimmer. Not that he ever loses sight of the overall shape of this movement. The crescendo builds inexorably, the string melody growing in strength until it reaches the crest of the wave. When the opening music returns, after the silence, it feels as if we are in a beautiful dream.

Tamás Vásáry (conductor)

Chandos CHAN 8913

The now disbanded Bournemouth Sinfonietta, a chamber orchestra sibling of the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, is on sparkling form for Respighi, with excellent recorded sound. The bright colours and rhythmic drive of ‘Spring’ seem to come from the same world as Stravinsky’s Petrushka in conductor Tamás Vásáry’s hands, while he draws out the lyricism of ‘Adoration of the Magi‘. And while his ‘The Birth of Venus‘ is fast, none of the detail or delicacy is lost. The great hymn to beauty truly seems to emerge from a swirling sea.

Richard Hickox (conductor)

Collins Classics CC-1349

Richard Hickox relishes the rich colours of Respighi’s writing in this performance, and overall takes a more expansive view compared to Marriner. There’s an almost luxurious quality to the City of London Sinfonia’s expressive playing. If the central movement misses the last ounce of atmosphere, the magical delicacy of the rippling waves at the start of the third paves the way for a superbly characterised finale. Best of all is the sense of majesty and awe created here, ideally fit for a goddess making landfall on a giant seashell.

John Neschling (conductor)

BIS BIS-2250

There’s a gentler, more atmospheric feel to this Botticelli Triptych, which appears on the fifth instalment of John Neschling’s complete Respighi cycle. The Brazilian conductor and the Orchestre Philharmonique de Liège are perhaps at their finest in the nativity sequence, with eloquent wind solos. Veni, veni Emmanuel is imbued with a hauntingly ‘ancient’ feel that recalls Vaughan Williams and his Tallis Fantasia. And although tempos are on the slower side, the performance never drags. In fact, there’s a welcome spaciousness that allows the music to breathe.

And one to avoid…

There are good things about this 2015 recording from the Orchestra Sinfonica di Roma and Francesco La Vecchia. Not least, it comes as part of the only current complete recorded set of Respighi’s orchestral works (Brilliant Classics), which may well be more than enough of an appeal to listeners. Yet compared to other recordings, La Vecchia’s take feels rather unrefined and raw – including what sounds like a rogue oboe note at the end of ‘Spring’.