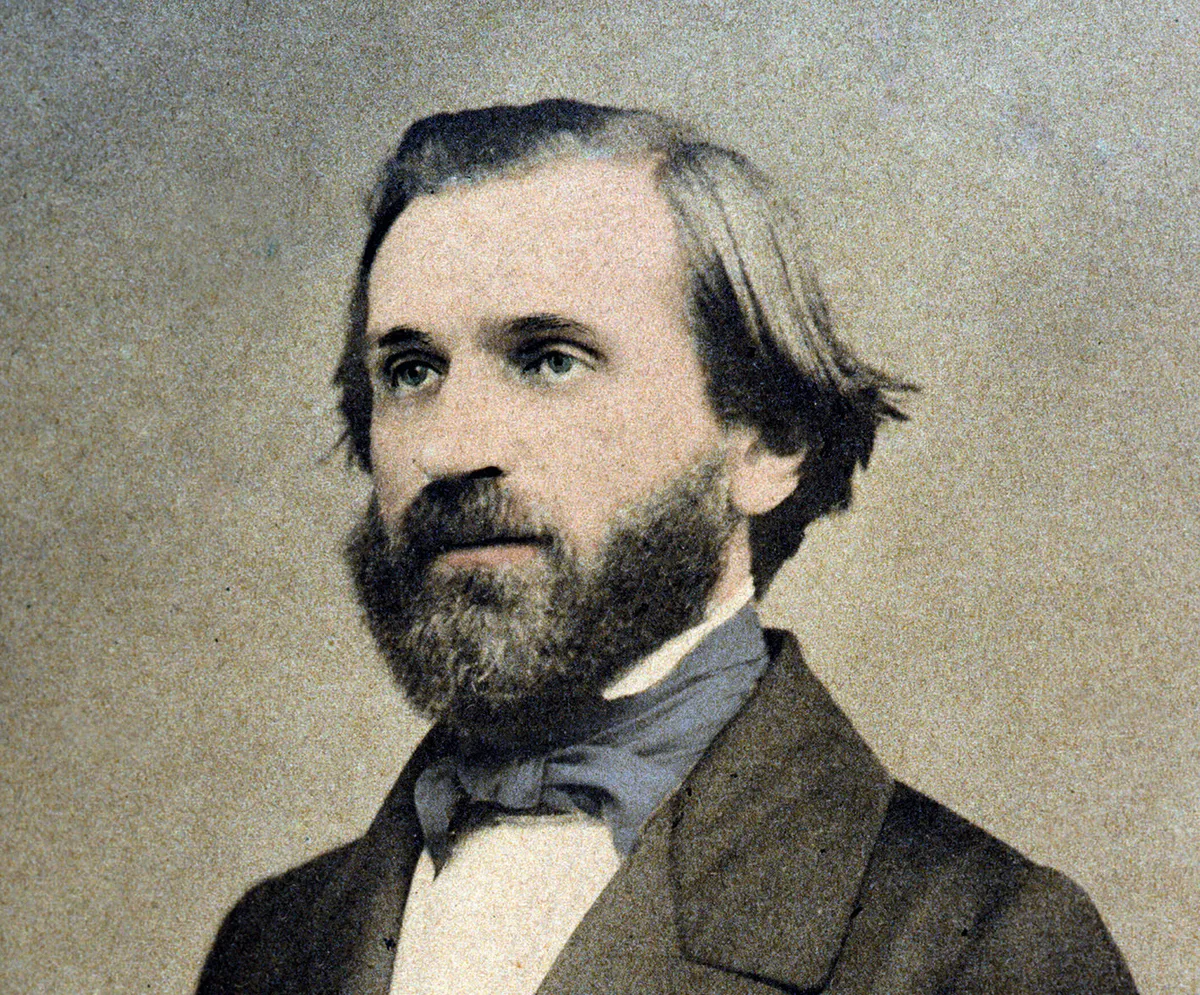

When the 37-year-old Giuseppe Verdi wrote Rigoletto, he was on the cusp of hitting the big time.

Although he had already seen 15 operas premiered at theatres across Italy plus Paris and London, of those only Nabucco (1842) and Macbeth (1847) would go on to be ranked among his major achievements.

Forging his early career in Milan, he had endured tragedy in his mid-20s with the death of both his children and then his beloved first wife Margherita. When his second opera Un giorno di regno flopped soon after, he vowed to give up composing, but the resounding success of Nabucco restored his belief and led to a prolonged period of fevered activity.

When was Verdi's Rigoletto first performed?

First performed at the Teatro La Fenice in Venice on 11 March 1851, Rigoletto is widely held to mark the commencement of Verdi’s ‘middle-period’, when his conception of opera and his blend of compositional discipline combined with an increasing freedom of form to achieve a heightened artistic level: he followed it with Il trovatore and La traviata, both premiered in 1853.

Rigoletto is also the first of Verdi’s works never to have left the repertoire: according to statistics compiled by the website Operabase.com, it remains in the top ten of the world’s most popular operas to this day.

- Don Carlos: the best recordings of Giuseppe Verdi's greatest opera

- The 20 greatest operas of all time

Yet despite its instant and ongoing success, it was a controversial project that brought Verdi – not for the first or last time – into conflict with the strict Italian censorship.

What works inspired Rigoletto?

The problems began with the subject, drawn from the play Le roi s’amuse by the French dramatist Victor Hugo (1802-85) – one of the most exciting talents on the contemporary scene, but equally a writer determined to challenge cultural barriers and especially the powers-that-be. Hugo’s bold Hernani had descended into something approaching a pitched battle at the play’s first night at the Comédie Française in Paris in 1830; Verdi would set it to music – also for Venice – in 1844 as Ernani.

Having received just one single performance in Paris in 1832 before being unceremoniously banned, Le roi s’amuse was even more controversial. The King has his Fun – as one might translate the title – is set at the court of French king François I (1494-1547), an individual portrayed by Hugo as concerned with nothing but his own sexual gratification at whatever cost to others. His jester Triboulet – another historical figure – encourages this cruelty, though after the monarch has raped the jester’s daughter Blanche, Triboulet determines to have the king assassinated.

What is Verdi's Rigoletto about?

Verdi was fired by the potential of the subject, which he thought ‘grand and immense,’ with a central character ‘who is one of the greatest creations that the theatre can boast of, in any country and in all history’. It was partly the jester’s divided nature that excited Verdi.

At the king’s court he is a figure of pure malice, coruscating in his malicious responses to the courtiers (who unsurprisingly seek revenge) while encouraging the King’s worst excesses - even proposing that François has the husband of a woman he lusts after executed to attain his desires. At home, though, with the daughter whom he conceals in secret to protect her from the widespread viciousness that he himself has helped foster, he is a father whose love is unbounded.

Acting as the local censor, the Austrian Governor of Venice, however, was having none of it, turning the opera down as ‘a repugnant example of immorality and obscene triviality’. As they must have understood that they would need to, Verdi and his librettist Francesco Piave made concessions: instead of a king of France, François became an unnamed 16th-century Duke of Mantua; since the Gonzaga dynasty who ruled Mantua had died out, they could hardly complain. Other names were changed to match the new Italian setting: thus Triboulet became Rigoletto and Blanche Gilda.

At the end of the opening scene, both the Duke and Rigoletto are cursed by the nobleman Monterone, whose daughter has been dishonoured by the former (though the Duke, unlike the jester, seems to escape its effect). The curse is crucial both dramatically and musically – its theme opens the opera’s prelude and recurs throughout, and at one stage the opera itself was going to be called La maledizione.

As Verdi wrote to Piave: ‘The entire story is in that curse, which also becomes a moral judgement. An unhappy father who weeps over his daughter’s stolen honour, derided by a court jester whom the father curses, and this curse catches up with the jester in a terrifying manner; it seems to me moral and great, supremely great.’

In purely artistic terms, what Verdi achieved in his score marked a significant step forward in his ongoing quest to make his music serve the drama, compressing it into something tense and gripping. In addition, throughout the score runs a long sequence of numbers – arias or monologues for the individual characters, duets (Verdi once said that he conceived the opera as a series of duets), plus a brilliantly characterised quartet in the final act and, most famously of all, the once-heard, never-forgotten Duke’s song ‘La donna è mobile’, all of which are still familiar as popular extracts; yet these ‘hit numbers’ coalesce into something even greater.

Given its longstanding currency in the repertoire of many great opera houses and individual singers, it is scarcely surprising that a ‘complete’ (in fact little more than a selection of popular highlights) recording of Rigoletto was made as early as 1907, or that since then there have well over two hundred more, both live and made in the studio, in all available formats. From the early days of the LP come several particularly noteworthy performances, musically distinguished if not necessarily in the best sound.

Verdi's Rigoletto: best recordings

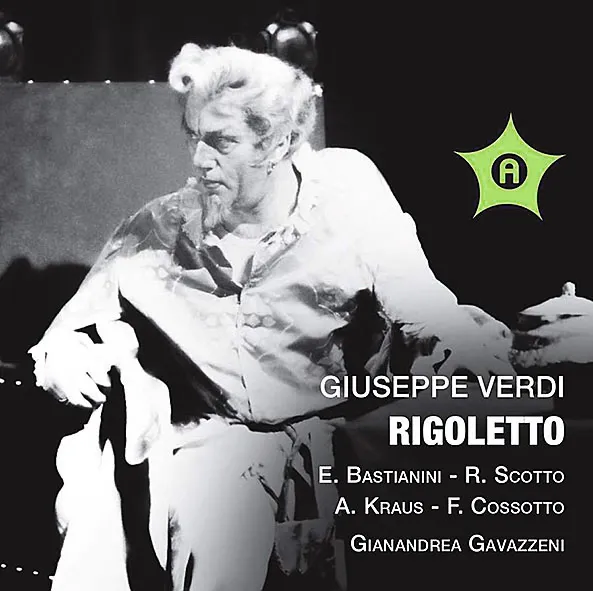

Gianandrea Gavazzeni (conductor) Ettore Bastianini (Rigoletto), Renata Scotto (Gilda) et al; Orchestra e Coro del Maggio Musicale Fiorentino Andromeda ANDRCD 9095

Finding a recording that provides all the qualities ideally needed for this difficult opera is not easy: the three principal roles all offer exceptional challenges. So while it may not have the finest sound, the sheer theatricality of the 1960 performance in which the forces of the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino are led by Gianandrea Gavazzeni proves tremendously persuasive.

An easy figure to underrate, Gavazzeni (1909-96) was an Italian maestro of the old school of tremendous range and experience, who conducted a vast repertoire over many decades: his reading bristles with vitality and conviction borne of a long tradition, here represented with compete authenticity.

Each of the principals brings special qualities to the cast. A bass turned baritone, Ettore Bastianini would die at the age of 44 in 1967 of throat cancer, which was initially diagnosed in 1962 – two years after his recording of the opera’s title-role was made.

He remains a controversial singer. While he could at times handle Verdi’s lines roughly – vocally fearless, he is sometimes incautious – at his best he is an exciting performer whose grand-scale Rigoletto is founded on bags of tonal and psychological variety, conveying the internal side of the character as well as his contrasting public face.

Captured in better voice that on his later set conducted by Julius Rudel, tenor Alfredo Kraus has all the easy-going elegance required for the Duke’s vocal line, as well as the lightness of spirit essential for a character who takes nothing seriously. Playing a morally deplorable human being, Kraus himself is nevertheless a paragon of vocal virtue, seductive and winning.

Of a similar age, soprano Renato Scotto captures the initial youthful optimism and emotional intensity – and equally the vulnerability – of the over-sheltered Gilda in a treasurable performance that finds her on peak form: in what is a considerable artistic achievement, she even makes it sound easy.

There are strong supporting interpretations from bass Ivo Vinco’s Sparafucile and mezzo Fiorenza Cossotto’s Maddalena, while there is nothing secondary about the Monterone of baritone Silvio Maionica, who puts the fear of God into Rigoletto with his furious interruption of the Duke’s party and subsequent curse.

The chorus delivers with energy and to spare. Orchestrally, there may be neater accounts of the score available, but what character and empathy with Verdi’s writing these Florentine players demonstrate!

Tullio Serafin (conductor)

Warner Classics 2564634095

A 1955 recording that retains classic status stars Tito Gobbi in the title role, offering a potent range of colour and delivery. Maria Callas brings interpretative insight to bear on every one of Gilda’s phrases, while Giuseppe di Stefano – even if inclined to be overemphatic – swaggers confidently as the Duke. Plinio Clabassi makes a sonorous Monterone while Nicola Zaccaria voices a sepulchral Sparafucile. Collaborating with the chorus and orchestra of La Scala, Italian maestro Serafin maintains a keen sense of style, even with some standard cuts, including the Duke’s ‘Possente amor.’

Carlo Maria Giulini (conductor)

In better sound is the musically observant 1979 recording with Viennese forces under Giulini, whose command both of the work’s lyrical and dramatic elements demonstrates his focus and breadth. Piero Cappuccilli’s dignified account of Rigoletto makes a full impact. Offering lithe vocalism and plenty of character, Ileana Cotrubas’s Gilda is infinitely touching, while the security and certainty of artistic aim of Plácido Domingo’s Duke make up for a voice a shade heavy for the role. There is a proud Monterone from Kurt Moll, and both Nicolai Ghiaurov’s Sparafucile and Elena Obraztsova’s Maddalena are memorable.

(Deutsche Grammophon E457 7532)

Riccardo Chailly (conductor)

Despite some idiosyncrasies and sound effects (including laughter) that some may find intrusive, Jean-Pierre Ponnelle’s 1983 film has considerable visual appeal in its lavish and historically accurate Mantuan settings, while the Viennese studio recording under Riccardo Chailly is strikingly good. Ingvar Wixell’s doubling of Rigoletto and Monterone – roles with an identical range – works well, while Luciano Pavarotti engages on every level with the Duke and Edita Gruberová’s impeccable coloratura skills are to the fore as Gilda. There’s dedicated support from Ferruccio Furlanetto’s Sparafucile and Victoria Vergara’s Maddalena.

(DG/Unitel 073 4166 (DVD))