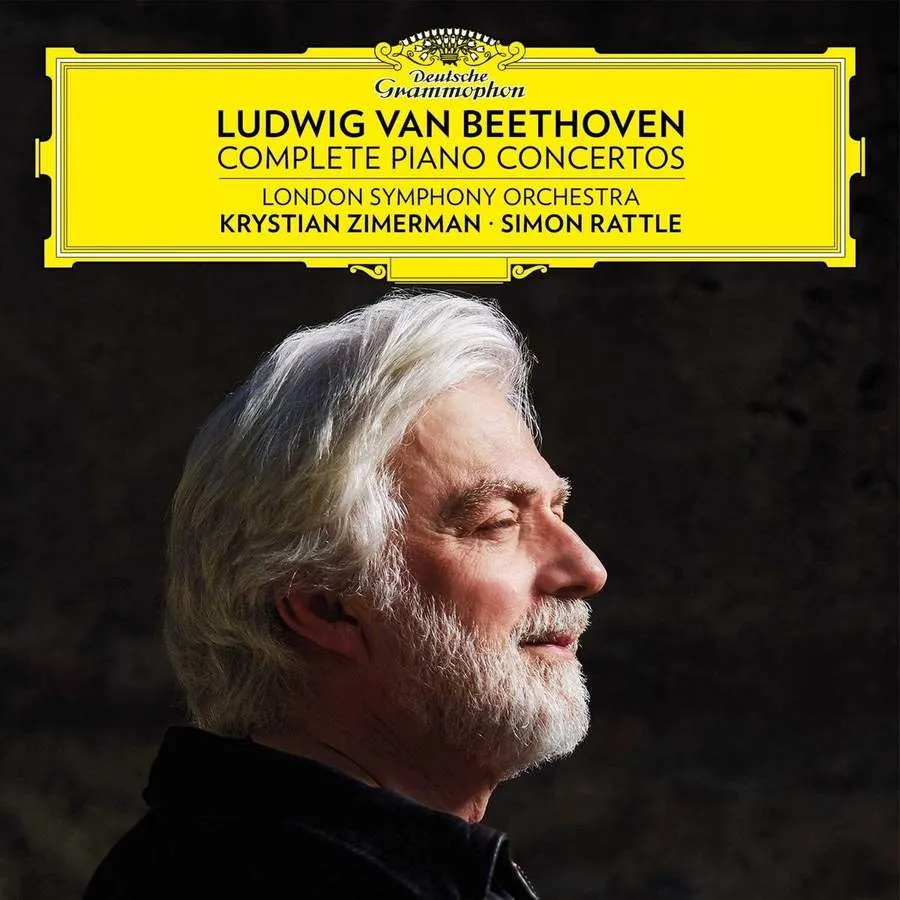

Beethoven Complete Piano Concertos Krystian Zimerman (piano); London Symphony Orchestra/Simon Rattle DG 483 9971 172:00 mins (3 discs)

It’s appropriate that the peak of Beethoven’s orchestral artistry should be scaled by two musicians also at the height of their powers: these performances are as near-definitive as I ever expect to hear. Krystian Zimerman, who has always ploughed a lonely furrow in defiance of convention, just gets better with the years; supported by the transparency and eloquence of his passage-work, his interpretations here have a fleet grace which takes the breath away. Simon Rattle, meanwhile, makes the perfect foil, though Zimerman, as reported in Jessica Duchen’s liner note, employs a different metaphor: ‘I don’t expect Simon to accompany me, yet he does, because he’s absolutely like a glove… he’s always there when he should be.’

These recordings were undertaken with approved Covid distancing, which in Rattle’s view is appropriate. ‘The orchestral set-up is fascinating because you have to send the music over long distances,’ he says. ‘Sometimes it feels like blowing smoke signals over a mountain. But the effort almost suits Beethoven. Struggle is part of the style. He is a composer who demands that everyone is straining every sinew, and who always asks more than you can give.’

Zimerman has enriched the mix by fitting his piano with several interchangeable keyboards, in an attempt to reflect the instruments Beethoven used. He discovered that the composer worked on a Walter instrument – whose keyboard invited a lighter touch than others – while composing the fourth concerto, so he has imported a Walter action for that piece.

Each of the works here brings its own particular pleasures. In the first concerto it’s the crystalline cadenza, the tender articulation of every bar in the Largo and the terpsichorean joie de vivre of the finale; the effect of this movement is repeatedly to evoke relative distances, from close-up to far away. In the second concerto – written first, and displaying Beethoven’s full-dress heroic mode – there is a particular pleasure which lies in the conversations between soloist and orchestra in the Adagio. In an atmosphere of bated-breath beauty, the soloist’s questions hang in the air with the orchestra answering them thoughtfully, while the energetically muscular Rondo dissolves all seriousness with a string of jokes.

The third concerto emerges with all its persuasiveness and nobility. It had its roots early in Beethoven’s career, with a gnomic sentence in a notebook pointing to the way he would later pursue a motif from the end of the first movement to its cadenza, and this performance tellingly exemplifies that echo; the Largo unfolds in something of a hushed trance.

Zimerman’s account of the first movement of the fourth concerto starts with gentle conversationality, but in the development it starts to unveil mysteries, with a magical series of downward-sweeping figurations. It then brings out the sheer theatricality of the music: the scales marching up and down the keyboard at the end of the first movement suggest curtains being drawn across a stage. The fifth concerto gets a reading which is ecstatically triumphal, and is full of lovely pianistic touches. In each work the London Symphony Orchestra rises splendidly to the occasion.

Michael Church