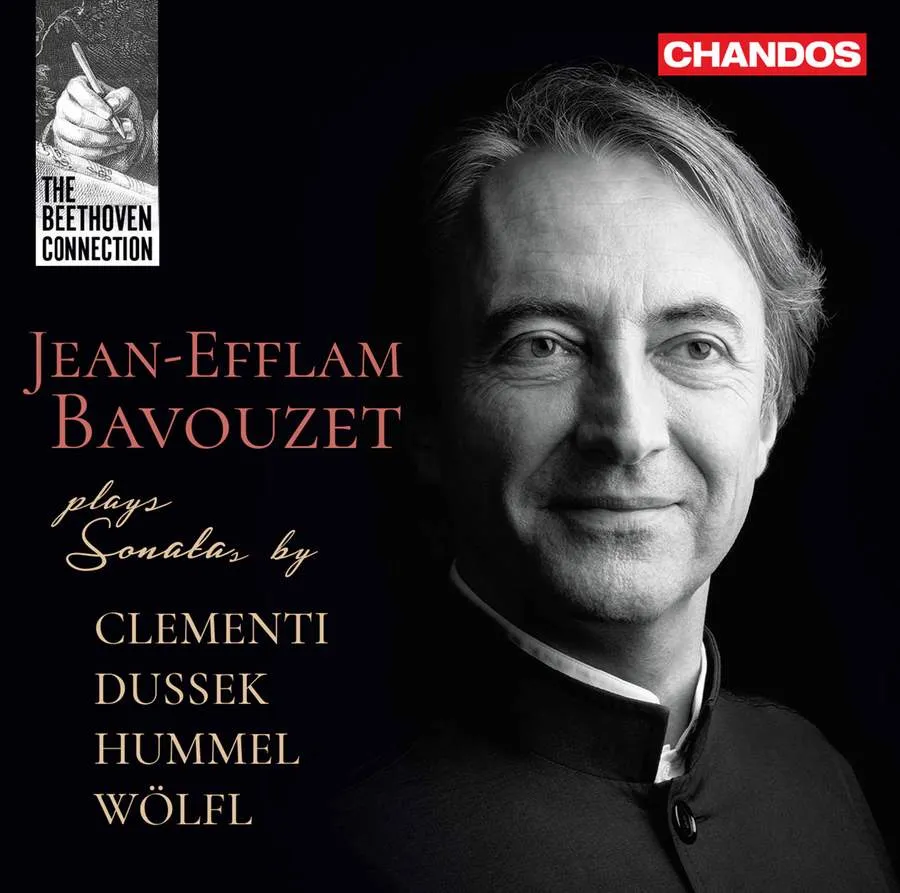

The Beethoven Connection Wölfl: Piano Sonata, Op. 33 No. 3 in E major; Clementi: Sonata in A major, Op. 50 No. 1; Hummel: Piano Sonata in F minor, Op. 20; Dussek: Piano Sonata No. 24 Op. 61 in F sharp minor ‘Elegie Harmonique’; Jean-Efflam Bavouzet: Musical Illustrations Jean-Efflam Bavouzet (piano) Chandos CHAN 20128 82.34 mins

This recording embodies a brilliant idea, brilliantly carried out. Beethoven’s revolutionary fire burned so This recording embodies a brilliant idea, brilliantly carried out. Beethoven’s revolutionary fire burned so brightly that all around him were cast into the shade: Jean-Efflam Bavouzet has reached into that shade to bring out sonatas by four other composers written during Beethoven’s fourth decade. All knew each other, all knew Beethoven, and three of them spent much time in London; as Bavouzet observes, their works, when laid alongside those of Beethoven, can give us a much better idea of the musical lingua franca of the day.

Each of the works which Bavouzet has programmed is a revelation, and reflects the fundamental changes which were taking place in pianism around the turn of the 19th century. He begins with a sonata by Joseph Wölfl: like all the other composers on this recording, Wölfl was a celebrated keyboard virtuoso, and once had a public duel with Beethoven, acquitting himself with honour; aided by his enormous hands, he brought off seemingly impossible virtuoso passages with ease, and like Beethoven he was a master-improviser. His Sonata Op. 33 No. 3 is high-spirited and dashingly Mozartian, and Bavouzet despatches it with verve; the Andante would make a lovely piece for young learners.

Beethoven ranked the sonatas of Muzio Clementi – who wrote 60 of them – higher than the sonatas of Mozart. Known as ‘the father of the pianoforte’, Clementi was the principal inventor of the ‘modern’ style, his trademarks including parallel octaves, sixths and thirds. His Sonata Op. 50 No. 1 is by any standards a major work, with its concluding Allegro vivace coming over with Beethovenian force. The majestic first movement pursues an intriguingly exploratory path: the twists and turns of its journey are full of surprises, and its effects have an entrancing delicacy; the Adagio recalls a Bach sarabande, yet it’s harmonically audacious.

Johan Nepomuk Hummel was a child prodigy and, like Wölfl, a pupil of Mozart; Haydn was one of his admirers, and arranged for him to take over from him as orchestral director to Prince Esterházy at Eisenstadt. Hummel was famed for the beguiling elegance of his playing, and his Sonata No. 3 in F minor, as Bavouzet plays it, corroborates that fact. The sweetness and transparency of the opening Allegro has winning charm; the finale luxuriates in its own easy virtuosity.

Jan Ladislav Dussek hailed from Bohemia, but political turbulence forced him to travel ceaselessly around Europe. His Sonata Op. 61, C211, published by Clementi, is another outright winner, looking forward to Schumann in its impulsive discursiveness, and to Chopin in its effects; its finale is a ravishing display of joyfully contrapuntal lyricism.

Bavouzet finally lays selected tracks side by side to show how closely some of the techniques and procedures in these works mirrored those employed by Beethoven – the only difference being the absence of genius in these four supremely gifted craftsmen.

Michael Church