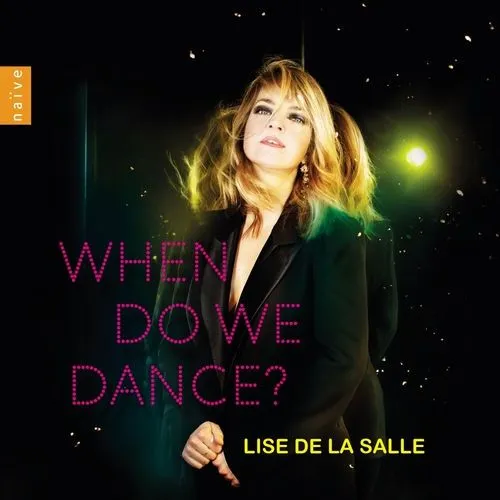

When Do We Dance? Gershwin: When Do We Dance?; Tatum: Tea for Two; Bolcom: Graceful Ghost Rag; Waller: Viper’s Drag; Piazzolla: Libertango; Ginastera: Danzas Argentinas, Op. 2; Falla: El amor brujo; Ravel: Valses nobles et sentimentales; Saint-Saëns: Étude en forme de valse; Debussy: Mazurka, L. 67; Bartók: Romanian Folk Dances; Stravinsky: Tango; Scriabin: Waltz in A flat major, Op. 38; Rachmaninov: Polka Italienne in E flat major Lise de la Salle (piano) Naïve V5468 73:08 mins

Born 33 years ago in Cherbourg, Lise de la Salle is a bit of an enigma. It’s an understatement to say she looks striking: she radiates bad-girl teenage wildness alternating with a timeless porcelain purity, and her big, widely-spaced eyes suggest an animal hyper-alertness which is richly borne out by her playing. When her fingers are filmed from above, as in the CD-DVD release Lise de la Salle: A Portrait, they move with a speed and precision not granted to those of ordinary mortals.

Her beginnings were fairly prodigious, but the variety of her teenage repertoire was more so, as were the accolades heaped on her recording of the first concertos of Liszt, Prokofiev, and Shostakovich when she was 20. Musically she’s a chameleon, capable of completely changing her colour at the drop of a hat, and that versatility is what makes this new recording such a success. She says that as a little girl she was always mad about dance, and regards its melding of rhythm and movement as ‘fundamental to life’. Wanting to celebrate it, she hit on a fertile historical period – 1850 to 1950 – as the focus for a century of dances from all round the world.

It’s a neat idea, which she carries out with panache. ‘Whether the pulse is stable or unstable, strong or discreet, slow or fast,’ she says, ‘the structure of every piece depends on the quality of its inner rhythm.’ She adds that she has huge respect for their composers’ scores: ‘I have tried to understand these pieces in order to make them mine.’

Her list of composers may look at first blush too heterogeneous, but in fact it works an absolute treat. At one end of her spectrum sit Art Tatum’s ‘Tea for Two’ and Fats Waller’s ‘Viper’s Drag’, and comparing her performances with those available to listen to on YouTube one finds that she has transcribed their performances, not only note for note but even in their tiniest inflections. Yet she manages to catch the spirit of the originals so accurately that, listening blind, you wouldn’t know who was playing: she and they have the same easy virtuosity, the same eagerness and appetite for life. At the other end of her spectrum sit Saint-Saëns’s crowd-pleaser Étude en forme de valse – in which de la Salle tosses out dazzling technical flourishes – and Ravel’s Valses nobles et sentimentales which she delivers with gentle grace.

In between there is a fascinating medley including some rarely-performed items – who knew Bolcom’s Graceful Ghost Rag, or Rachmaninov’s Polka Italienne? Three of Ginastera’s Danzas Argentinas – one edgy and frantic, one languid and lazy, one volcanically energised – sit beside de Falla’s Danza ritual del fuego. Bartók’s Romanian Folk Dances may be slightly over-domesticated, but they have winning charm and Stravinsky’s Tango – all chopped and squashed chords – may be anchored to the spot, but it builds a massive muscular tension in its three-minute span. This recording is a wonderful tour de force.

Michael Church