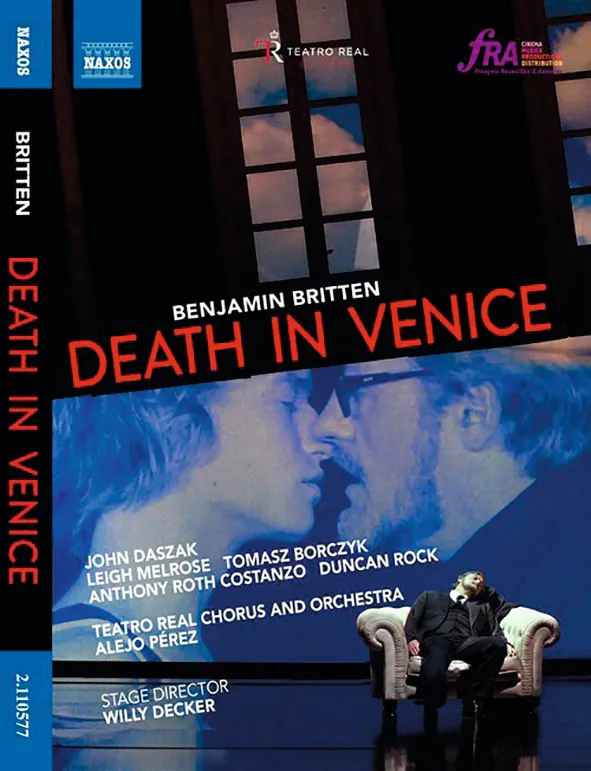

Britten Death in Venice John Daszak, Leigh Melrose, Tomasz Borczyk, Anthony Roth Costanzo, Duncan Rock; Teatro Real Chorus & Orchestra/Alejo Pérez; dir. Willy Decker (Madrid, 2014) Naxos DVD: 2.110577; Blu-ray: NBD0076V 152 mins

Death in Venice, Britten’s last opera, is in many ways the culmination of his work. In craft alone, there are the effortless ‘naturalistic’ effects he had learnt from scoring documentaries (a brushed snare drum evokes the sound of a steam ship), or the remarkable bell effects – ranging from evoking the clang of great bells in the ‘Overture’, to the tinkling bells that symbolise Tadzio and his young companions – that had haunted Britten’s music since his visit to Bali in the 1950s.

After so many disappointing productions, it’s exciting to watch one which casts a lurid new light on this disturbing opera and, more importantly, gives scope for two very fine singing actors. Director Willy Decker realises that a great deal of what happens is all in Aschenbach’s mind, freeing the production from the demands of straight realism. No matter that Aschenbach identifies and describes the mysterious Traveller without ever facing him: the way the latter first appears as if he were Aschenbach’s shadow makes clear he is one of several tempting voices within Aschenbach’s psyche which send the inspiration-starved writer teetering off course. The people of Venice are not so much presented as represented by luridly dressed and made up street boys and prostitutes (one of whom sings the strawberry seller’s lines, making clear from the start their symbolic character). And I cannot think of a more powerful and visceral staging of the travelling players’ show. All this, though, is icing on a cake whose substance is the outstanding performances by John Daszak, exuding well-meaning civilised weariness as Aschenbach, and the glinty-eyed, sinuous Leigh Melrose who plays and sings the various sinister characters who by turns torment and seduce Aschenbach into abandoning his Apollonian principles to give himself up to ‘chaos and sickness’.

Daniel Jaffé