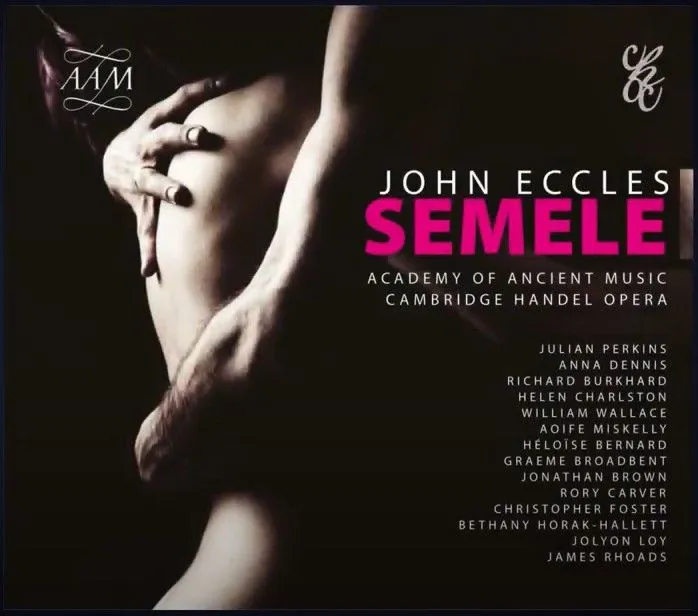

Eccles Semele Anna Dennis (soprano), Richard Burkhard (baritone), Helen Charlston (mezzo-soprano), Héloïse Bernard (soprano), Graeme Broadbent (bass) et al; Cambridge Early Opera; Academy of Ancient Music/Julian Perkins AAM AAM012 121:27 mins

John Eccles’s sexy, sparkling opera bursts to life – finally! Shelved in 1706, Semele has never been professionally recorded, so this production was worth waiting for. Cast, band, director and sound are all top-notch, restoring Eccles’s score to its full glory.

The project grew out of Julian Perkins’s November 2019 Cambridge Handel Opera Company concert performance, with rising-star soloists singing alongside the more seasoned professional names.

It’s astonishing that Eccles’s Semele is obscure: the libretto, by William Congreve, is as yummy as Eccles’s music. Adapting Ovid, Congreve has Semele joyously join Jupiter in illicit love, escaping thereby an unwanted earthly match. Jupiter’s enraged wife Juno, in the guise of Semele’s sister, goads Semele to trap Jupiter into granting her wish that he show himself to her as a god, which kills her.

Thanks to Perkins’s deft casting, each principal’s vocalism and dramatis persona are wonderfully matched. As Semele, Anna Dennis is at first seductive in her delicacy, then frightening in her steely-toned ambition. Dark-timbred mezzo soprano Helen Charlston’s Juno flares magnificently, unafraid to sound ugly when furious. Baritone Richard Burkhard captures Congreve’s sensual yet thoughtful Jupiter, texturing every word. The show-stealer is soprano Héloïse Bernard who, as Juno’s servant Iris, forges riveting moments from modest material, such as ‘Thither Flora the Fair’. In this brief chaconne, Bernard drapes each stanza in increasingly gorgeous embellishments, dropping dramatically into chest register for her last verse.

The Academy of Ancient Music’s playing is just as fascinating. Perkins directs from the harpsichord with a demonic intensity. When individual band members take over the storytelling, their solos gild Eccles’s invention with their own. Lost instrumental numbers – symphonies, dances, ritornellos – known on the page only from stage directions, are here taken from other Eccles compositions. They give the AAM further opportunity to strut, from the regal Overture (from his Rinaldo and Armida), to the sparkling ‘Dance of the Zephyrs’ (from his Aires).

Eccles’s solo and instrumental writing are both exquisite, but he experiments most boldly in his vocal ensembles. In these, catchy tunes and rhythms belie the sophistication of counterpoint and motivic networking as entwined solo voices typically yield to regal choruses or symphonies. Perkins commands a gamut of responses to the ensembles’ charms, from crystal-clear voicing to big, fat homophonic swells. The Act I quartet ‘Why dost thou thus untimely grieve?’, in which four characters each express a different foreboding, captures both Eccles’s originality and the performers’ brilliance: after introducing the common theme, the soloists, taking their cue from Perkins’s keyboard playing, gently decelerate their points of imitation to bring the quartet to a brooding close.

With early career vocalists among the cast, there are minor imperfections, but this is a superb reconstruction of a lost Eccles masterpiece.

Berta Joncus