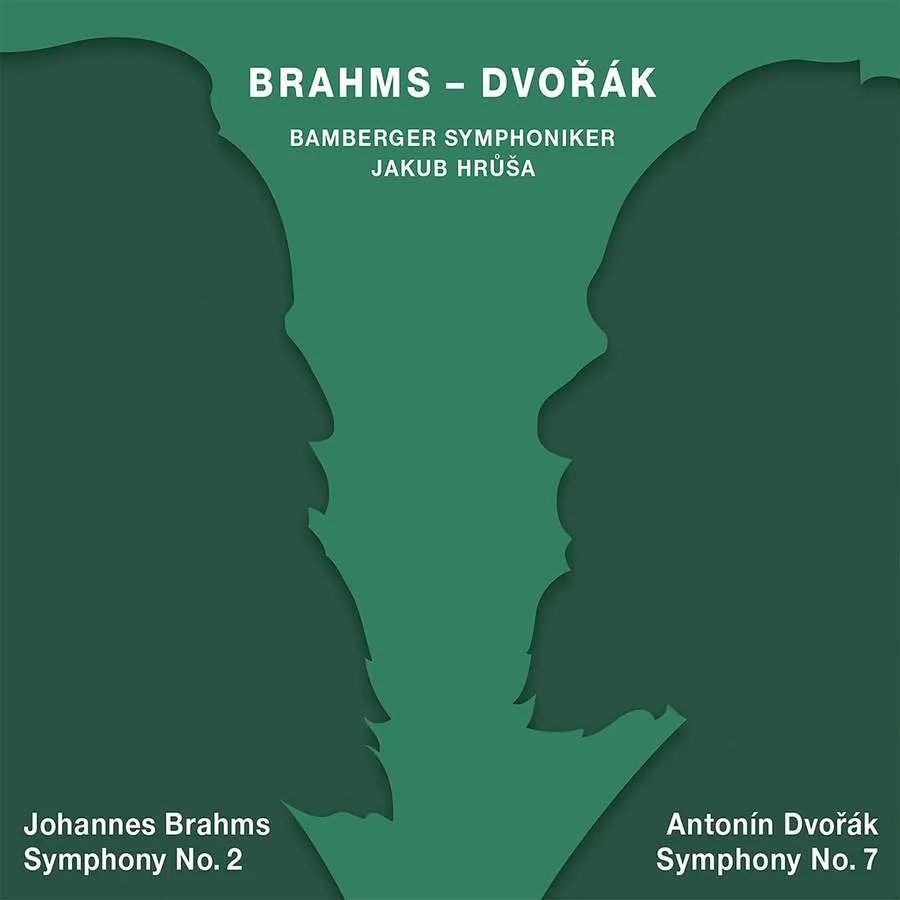

Brahms • Dvořák Brahms: Symphonies Nos 1 & 2; Dvořák: Symphonies Nos 6 & 7 etc Bamberg Symphony Orchestra/Jakub Hrůša Tudor TUD1741 108:31 (2 discs) & TUD1742 84:33 mins (2 discs)

Jakub Hrůša and the Bamberger Symphoniker brought out their first release in this intriguing survey of Brahms and Dvořák symphonies some years ago to highly critical acclaim. An equally impressive sequel followed some months later. Now, after a slight hiatus, we can at last enjoy the generously packaged completed cycle in outstanding sound.

I have already commented upon the great advantage this particular series offers in enabling the listener to engage in a closer appreciation of the complex musical relationship that existed between these two formidable composers. Hearing Brahms’s Second and Dvořák’s Sixth side by side, for example, demonstrates a fascinating cross-fertilisation of influences It’s fascinating to discover that some of the overtly Brahmsian melodic and harmonic features in the Dvořák are matched by passages of lighter almost Dvořákian orchestral scoring in the Brahms.

Nevertheless, discovering elements of potentially shared musical values is merely of academic interest and what really matters is whether the quality of these performances matches up to the formidable competition that is already available. Fortunately, Hrůša, served by wonderfully refined orchestral playing from the Bamberger Symphoniker, has a great deal to say about all these works. The two Dvořák symphonies are particularly exciting. Hrůša injects lots of energy and colour into the outer movements of the Sixth. The Adagio, which in inferior performances can often meander, is totally riveting with Hrůša maximising variety of interest and drawing out all the subtleties of Dvořák’s writing.

The Seventh Symphony is no less compelling, a performance teeming with fierce intensity, especially in the Finale. As in previous releases by these performers, I noted Hrůša’s painstaking efforts to follow Dvořák’s scrupulously placed dynamic markings to the letter. One notable example appears in the Furiant third movement of the Sixth where the composer specifically asks for a blending between horns and cellos, a textural subtlety that is all too frequently ignored by others.

The Brahms performances are more likely to divide opinion. Those wanting a high-voltage stormy approach to the First Symphony might feel that Hrůša’s lyrical and refined interpretation in the outer movements robs the music of its rougher Beethovenian edges. I would argue, however, that going for bluster at every full orchestral tutti becomes counter-productive to Hrůša’s main concern with developing a cumulative sense of tension. There’s no doubt that conductor and orchestra map out the drama effectively enough in the Finale to make the hard-won optimism of the closing bars sound entirely convincing. A similar carefully negotiated conception of long-term structure works just as convincingly in the expansive first movement of the Second Symphony, the dramatic and sinister entry of the brass in the middle of the development section sounding particularly ominous.

The idea of supplementing Brahms’s orchestrations of three of his Hungarian Dances to the performance of the First Symphony and Dvořák’s equally sparkling instrumentation of Nos 17-21 from the same set to the Czech composer’s Sixth is welcome, especially in such effervescent performances as these.

Erik Levi