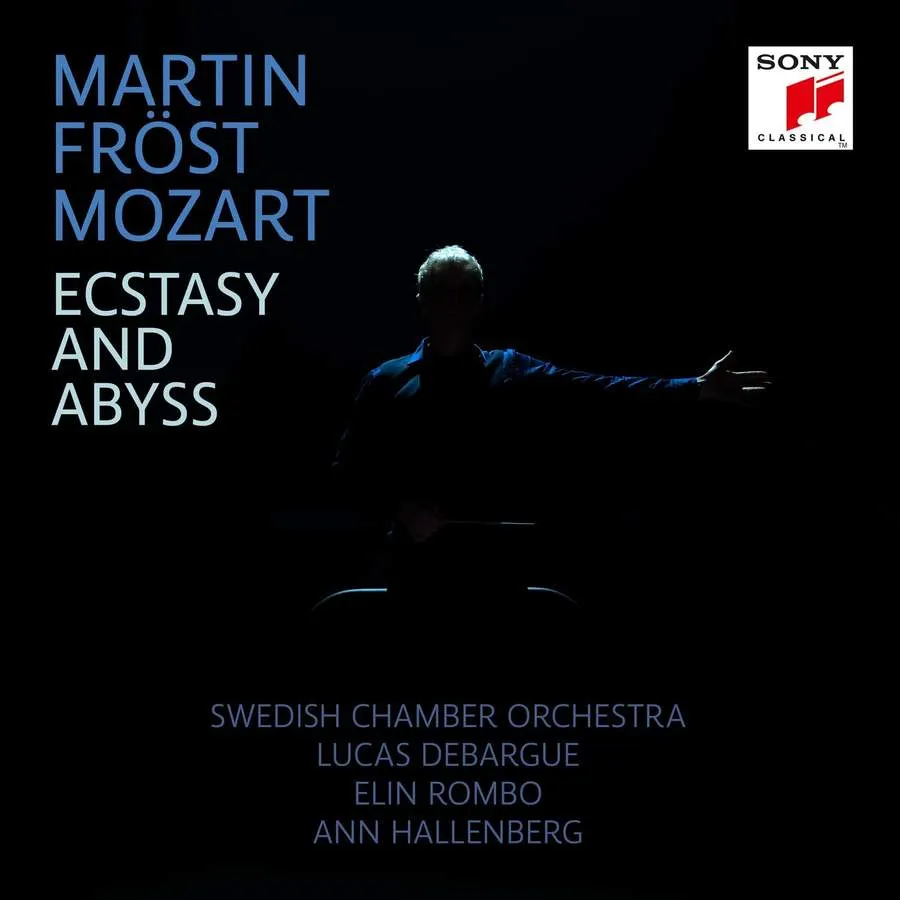

Mozart – Ecstasy and Abyss Symphonies Nos 38 (‘Prague’) & 41 (‘Jupiter’); Piano Concerto No. 25 in C, K503; Clarinet Concerto; ‘Ch’io mi scordi di te?... Non temer, amato bene’, K505*; La clemenza di Tito – ‘Parto, parto, ma tu ben mio’** *Elin Rombo (soprano), **Ann Hallenberg (mezzo-soprano), Lucas Debargue (piano); Swedish Chamber Orchestra/Martin Fröst (clarinet) Sony Classical 19658772252 139:14 mins (2 discs)

A nicely planned scheme: each of the two discs has a symphony, an aria and a concerto, the first featuring the piano, the second featuring the basset clarinet. The presiding genius is clarinettist and director Martin Fröst, who contributes a touching note about our need for Mozart’s ambiguous genius in these troubled times.

Choosing works performed in the years 1789 and 1791 (though not all written in those years) Fröst draws transparent yet impassioned performances from the Swedish Chamber Orchestra. The title ‘Ecstasy and Abyss’ perhaps oversells it, since there are few moments of abyss once we are past the chilling D minor introduction to the ‘Prague’ Symphony: the Andante of that symphony flows sunnily at a Norrington-type tempo. The ‘Jupiter’ starts with contrasted tempos à la Harnoncourt; you are likely to jump out of your seat at the fierceness of the off-beat chords in the Andante cantabile, and Fröst has an odd way of pulling on the brakes at the ends of phrases (like at bars 95 and 242 of the ‘Prague’ first movement).

But there are countless thoughtful and stimulating details to admire. Lucas Debargue is rather a plain pianist in the C major Concerto but a good partner to soprano Elin Rombo, a little too full-voiced for my taste in ‘Ch’io scordi di te?’. Mezzo Ann Hallenberg is absolutely ideal in the Clemenza di Tito aria ‘Parto, parto’. And it is surely only fair for Fröst to claim the final place with the Clarinet Concerto (his third recording), using the resonant lower range of the basset clarinet, at once light-toned, wistful in the Adagio, and bubbling over with gentle energy in the final ‘Rondo’.

Nicholas Kenyon