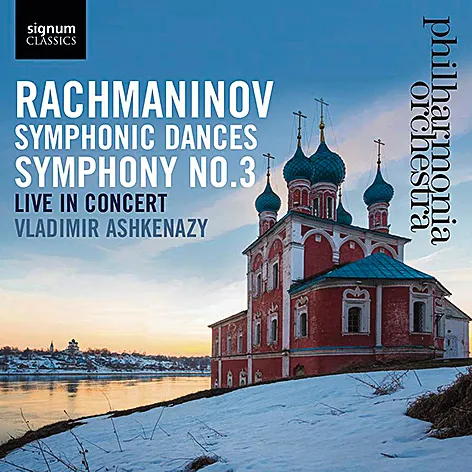

Rachmaninov Symphony No. 3 in A minor; Symphonic Dances Philharmonia Orchestra/Vladimir Ashkenazy Signum Classics SIGCD 540 77:34 mins

As a conductor Vladimir Ashkenazy scored one of his earliest recorded successes with Rachmaninov’s symphonic cycle, captured in resplendent sound by Decca’s engineers. The orchestra on that occasion was the Concertgebouw, whose luxurious opulence combined with Ashkenazy’s thrusting urgency to create readings balanced tantalisingly somewhere between Haitink-like majestic poise and a fiery, off-the-leash spontaneity reminiscent of Evgeny Svetlanov.

By comparison, the Philharmonia produces a leaner, more transparent sound, captured ‘live’ with almost tactile precision and accuracy by technical wizards Andrew Cornall and Jonathan Stokes in London’s Royal Festival Hall. This suits Ashkenazy’s latest take on the Third Symphony to perfection, which exchanges the urgently romantic thrust of the 1980s for a poetically subtle inner glow. The music’s distinct Russianness is experienced at a much deeper level this time around; so too its indebtedness to the New World, where Rachmaninov had settled, completing the work there in 1936. Ironically, America failed initially to appreciate the music’s economical restraint, while Russia simply turned its back, public performances of Rachmaninov’s music being at that time banned in the Soviet Union following his well-publicised hostile comments about the regime.

Shortly before starting work on his final magnum opus, the Symphonic Dances, Rachmaninov confessed in an interview: ‘I cannot cast out the old way of writing, and I cannot acquire the new.’ As if in direct response, Ashkenazy conducts a performance that whilst lacking nothing in elemental Russian intensity, possesses an almost Hindemith-like, neoclassical equilibrium, making the opening movement’s autumnally reflective coda feel all the more poignant in context. If Ashkenazy’s earlier account was more about emotions and feelings, here one can almost sense him thinking out loud.

Julian Haylock