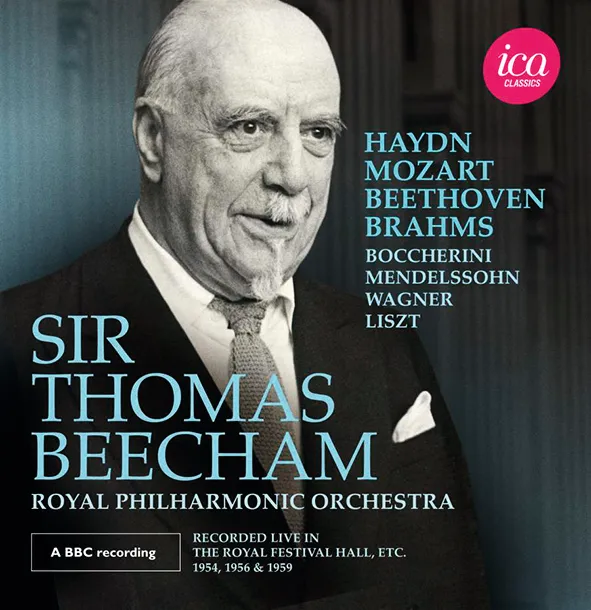

Sir Thomas Beecham Beethoven: Symphony No. 2; Brahms: Symphony No. 2; Haydn: Symphonies Nos 99 & 101; Liszt: A Faust Symphony; Mendelssohn: A Midsummer Night’s Dream Overture; Mozart: Symphonies Nos 36 (Linz) & 39, etc Alexander Young (tenor); Beecham Choral Society; Royal Philharmonic Orchestra/Thomas Beecham ICA ICAC5148 274:37mins (4 discs)

Recorded expertly by the BBC, mostly at the Royal Festival Hall between 1954 and 1959, these mono live recordings with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra capture the essence of Beecham’s final years with an infectious vitality not always encountered in the studio equivalents (fine though they are). Although Beecham was always keen to imbue his studio recordings with an urgent sense of spontaneity, his mercurial personality was almost invariably at its most beguiling live in concert.

One senses an extra degree of imperativeness in gripping performances of Haydn’s symphonies Nos 99 and 101, which by comparison with Beecham’s studio accounts for EMI (now Warner) dating from the same period, lean more towards vibrant authority and majestic sweep than twinkle-in the-eye breeziness and charm. Beecham does tend, however, to make rather a meal of Boccherini’s delightful G521 Sinfonia, which lacks the iridescent sparkle of Carlo Maria Giulini’s contemporaneous studio account with the Philharmonia for EMI/Warner Classics.

Beecham is very much back on form with 1954 performances of Mozart’s Linz and K543 (No. 39) symphonies, lithely played and recorded, which erupt in joyous finales whose captivating effervescence makes questions of authenticity a glorious irrelevance. Of the two overtures included here, Mendelssohn’s magical A Midsummer Night’s Dream sounds surprisingly a shade earthbound, whereas Wagner’s Flying Dutchman sails the high seas with imperious swagger and charisma.

The three remaining symphonies in this fine four-disc collection, are also well worth hearing. Beethoven’s Second and Liszt’s Faust were recorded at the same concert on 14 November 1956, the former playfully youthful and refreshingly unmannered, the latter more emotionally immediate and imposing than the studio account of three years later.

Brahms is not a composer automatically associated with Beecham, but on the evidence of this radiantly affectionate 1959 performance of the Second Symphony, he had – notwithstanding his oft-repeated waspish comments about that composer – a profound instinct for the German’s autumnal reflectiveness.

Julian Haylock